Introduction

The Charity bill, through Belgian eyes it is a subject that is fairly easy to understand. Explaining the concept to international students, however, is a much more difficult task. After all, it is not an isolated event, but something that can only be understood by looking at the complex political history and the struggles between the different movements. Belgium is simply not the most unequivocal country politically speaking. We saw this more recently (2010-2011) when Belgium broke the world record for being without a government for the longest time.

The video above offers a starting point for understanding how history has shaped the image of the Church in Belgium. It also briefly introduces the Charity Bill itself and, of course, the pros and cons. However, there are certain important questions that remain.

- What events in Belgium led to the proposal of the charity law and the broader conflict between Catholics and Liberals?

- How did different groups view the demonstrations?

I am going to try to offer a concise answer to these questions in the following paragraphs.

The Charity Bill itself

As discussed in the video, the Charity Bill entailed that monasteries would be assured possession of legacies that had been given to them to do good works. This measure was highly controversial. The Liberal Party and related strongly opposed it, arguing that it would further increase the Church’s power, something they were determined to resist.

As we saw in the video, there were both supporters and opponents of the Bill. One notable supporter was François Guizot, a French politician and historian; who had been a determining figure in France during the constitutional monarchy of Louis-Philippe (1830-1848) and taught at the Sorbonne. His arguments in favour of the Church’s role in charity are particularly interesting and merit closer examination. In his work ‘La Belgique et le roi Léopold’, Guizot outlines several reasons why he believed charity should fall especially within the Church’s remit. By examining passages from this text, we gain a clearer understanding of his perspective.

| |||

| Guizot, F. (1857). La Belgique et le roi Léopold en 1857, suivi de la loi de la charité en Belgique | et de l'appréciation politique de la même loi. Librairie Polytechnique de A. Decq, (p. 10). |

One telling passage (in translation) reads:

Outside this system, which dreamers, whether honest or perverse, can support, in which we have sometimes gone further than we would soon have liked to have done, but which has never been and probably never will be rigorously applied; outside this system, I say, it is private charity which, by general admission, is placed in the front line for the relief of misery.

In other words, Guizot argues that the state is inherently ill-suited to regulate charity rigorously or effectively. He sees private charity, especially Church-run initiatives, as better placed to respond to human need directly. For him this was not just a practical matter, but something widely accepted in society at the time. Another key passage clarifies his view even further:

For charity in general, freedom is almost a matter of natural right; it is the least we can do when making donations and sacrifices is to do so as we see fit. For religious charity, freedom seems even more of a right and more necessary; to hinder it in the choice of its means of action is to prohibit its very action: it must determine its own course to be sure of reaching its goal. You paralyse it if you claim to prescribe the paths it must take and the hands through which it must act.

Here, Guizot makes a principled argument about freedom. He claims that charity is most genuine and effective when it’s freely given and freely organised. In his view, state control over religious charity would destroy its essence, preventing it from choosing the most effective ways to help those in need.

For supporters of the Charity Bill, arguments like Guizot’s offered a moral and more philosophical justification for ensuring that the Church retained a central role in charitable work. Opponents, however, saw this as a threat to the secular state and to efforts to limit the Church’s influence in Belgian society. (4)

The demonstrations

One of the most interesting aspects of this period, in my opinion, are the demonstrations that arose in response to the proposed Charity Bill. These public protests were a big part of the political debate, as opponents sought to put pressure on lawmakers to reject the Bill. How exactly were these demonstrations actually perceived at the time? The answer is complex. Even though they gave a wider voice to the liberal concerns about the Bill, they also drew quite a lot of criticism. For example, in the print at the top of this post, we can see that the demonstrators were not always seen in a positive light.

I am certainly no expert when it comes to interpretation of prints, but the print I examined clearly does not give a positive impression of the protesters. One could interpret the bird of prey as the wild, aggressive protesters coming onto the streets and the sheep could be seen as a symbol of gentleness and innocence, in this case the Church. When we turn to the accompanying article, the negative tone becomes even more explicit. Words such as ‘infuriated mob’ and ‘barbarous shouts and yells’ are used to talk about the people that are coming down on the streets. The article also contains the phrase: ‘With these insults and injuries have the ungrateful Belgian burghers repaid the spiritual beneficence of their priests and bishops’. This is clearly a way to cast the demonstrators in a bad way. Even the king of the time, Leopold, is not spared. He is labelled ‘the heretic Leopold’, suggesting betrayal of the Catholic faith. Altogether, the image and article reveal how strongly polarised the debate was. For many Catholic commentators, the demonstrations were not a legitimate form of civic expression but a sign of heresy. (5)

|

| Persecution in Belgium. (1857). Punch, Or The London Charivari, 235, Europeana.eu. |

When l looked into how the demonstrations were described in newspapers of that time, I found several relevant articles. Unsurprisingly, the negative is always more interesting than the positive for papers, because it makes for more compelling headlines and stories. Much of what I found, therefore, was the negative side of the demonstrations. The first newspaper, is a Catholic newspaper, called ‘Courrier De L'escaut’. In one of its issues, it republished a piece of an article from 'Le Journal d'Anvers’, describing the manifestations as simply ‘stupid’. (6)

|

| Revue Politique. (1857, 11 juni). Courrier de L’escaut. Belgicapress. |

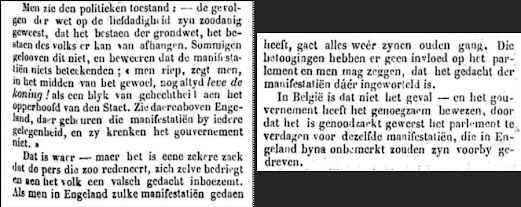

Another interesting perspective comes from the newspaper Het Handelsblad. The article compares the situation in Belgium to demonstrations in England. The newspaper indicates that demonstrations are far more common in England. As a result, the demonstrations have only a minor influence on actual political decision making. Here in Belgium, however, the situation is completely different. Demonstrations do not take place often and therefore they carry a lot more weight. This means that the demonstrations can indeed have a major influence on possible political decisions, and they must therefore be given due importance. (8)

|

| Gemeenteraed, Adres aen den koning. (1857, 9 juni). Het Handelsblad. Belgicapress. |

Introspection of the Eutopia connected learning community

One of the most rewarding aspects of this project was the opportunity to explain a subject that is relatively well known in Belgium to an international audience. It made me think a lot more about the history of my own country and made me realise just how complex and nuanced that history is. I also appreciated the fact that I could combine my interests in both law and history. It made me more confident about my choice to possibly study history after my law degree. The trip to England itself was an incredible experience. Both the city of Coventry and of course London are filled with history, culture and enormously beautiful architecture. Walking through these streets felt like stepping into the past and it gave me an appreciation for how much these cities hold historical stories.

The presentations from the other universities also provided a lot of insight. I was particularly struck by the work of the Slovenian students who had spent weeks or even months in the archives for their research. They gave me a certain drive to spend more time on research myself and visit the archives in Belgium for future projects. The most interesting part of the trip were simply the conversations with the other students. We have very little contact with international students in our course in Brussels. So, it was very enriching to now be able to talk to them for three days. We did not only talk about education but also our cultures, daily lives and even small differences that were surprisingly fascinating. For example, I was intrigued to learn that in some countries deadlines are flexible or that professors can be addressed by their first name.

Overall, this experience broadened my perspective both academic and personally. It left me eager to continue seeking out similar projects in the future.

By Emma Wittens

References

Video

- Aidan Gasquet, F. (z.d.). Henry VIII and the English Monasteries. Ballantyne Press.

- Coventry Cathedral of St Michael, medieval priory ruins. (z.d.). British Pilgrimage Trust.

- Guizot, F. (1857). La Belgique et le roi Léopold en 1857, suivi de la loi de la charité en Belgique et de l'appréciation politique de la même loi. Librairie Polytechnique de A. Decq, (p. 3-51).

- Laurent, F. (1858). L'église et l'état. Guyot.

- Van Elslande, R. (2014). De rechtvaardige rechters: een slecht bewaard geheim? Ghendtsche Tydinghen.

Blog

- Loobuyck, P., & Franken, L. (z.d.). Religious education in a plural, secularised society, a paradigm shift: Historical overview and current debates. Waxmann.

- Maes, A. (2010). Freemasonry as a patriotic society ? The 1830 Belgien revolution. REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña,

- De Laveleye, É. (1857). Le parti catholique en Belgique et la loi sur les fondations de charité. Libre Recherche: Revue Universelle.

- Guizot, F. (1857). La Belgique et le roi Léopold en 1857, suivi de la loi de la charité en Belgique et de l'appréciation politique de la même loi. Librairie Polytechnique de A. Decq, (p. 3-51).

- Persecution in Belgium. (1857). Punch, Or The London Charivari, 235. https://dn790006.ca.archive.org/0/items/punch32a33lemouoft/punch32a33lemouoft.pdf, Europeana.eu.

- Revue Politique. (1857, 11 juni). Courrier de L’escaut. Belgicapress.

- Revue politique. (1857, 11 juni). Journal de Bruxelles. Belgicapress.

- Gemeenteraed, Adres aen den koning. (1857, 9 juni). Het Handelsblad. Belgicapress.

Comments

Post a Comment