|

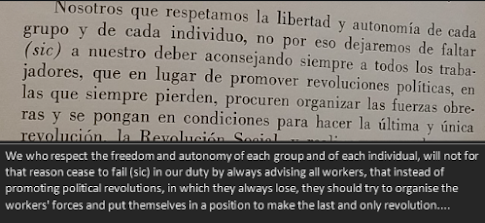

| Le Progrés Illustré, Lyon, 1892 |

Introduction

We now move on to warmer regions as we move our focus to Spain. Unlike Slovenia, Spain is a monarchy and a quasi-federated state as opposed to a unitary republic, however, they share some historic similarities, as both countries were ruled by the Habsburg dynasty at some point. The topic of my research is the 1892 Jerez uprising and its connection to the struggle for association and medieval rights. At first, I wanted to pick a specific event to research, however, the more I read about the history of assembly in Jerez, the more I was able to make the connection to old forms of assembly such as guilds, thus, slightly diverging from my main topic. Thanks to the large amount of digitalized documentation a large part of my research was done online, however I also had the duty and privilege of visiting the local archives in Jerez de la Frontera as well as receiving digitalized documents from the Polytechnic library in Belmez, as well as the Military Archives in Segovia. Doing my Erasmus exchange in Córdoba meant that I also had an abundant access to books and scholarly work on the topic in the University Libraries.

The city of Jerez is located in the far south of Spain. It is and was, the largest city in Cádiz province. The region in which its located was a prominent wine region ever since the 7th century and is located in the so-called “Sherry triangle”, which stretches from Sanlúcar de Barrameda, to Jerez and the port of Santa Maria. This region is the birth place of Sherry wine, which derives its name from the city of Jerez. Thus, assembly is deeply rooted in wine production.

In 1870 vines accounted for only 6% of land use, but provided the greatest income for both the region and the nation. Sherry wine originates from the Rhineland, coming from the palomino and Pedro Ximenez grapes where they were used for making Riesling, yet the chalky albariza soil in Andalusia gave it its unique taste. The production of wine required a lot of skilled labourers in skilled professions, such as pruners and coopers, who were well established in the medieval guild structure.

|

| Map of Cádiz province, J. Más; Gº., 1918 |

|

| Jerez a vista de pájaro. A. Guesdon, 1855 |

The Uprising

The uprising in question happened on the 8th of January 1892. Most sources attribute the uprising to hunger and the poor working conditions of field workers however the reasons go far deeper. To put it shortly public officials and bourgeois capitalists have a rich history of discouraging any form of assembly of workers and small business owners. Thus, the context of this uprising was no different. Since the 1891 May Day demonstrations, there had been numerous arrests of local workers in the hundreds including a local labour leader. Local authorities had created a news blackout on strikes and demonstrations in an effort to discourage coordinated labour activity, likewise in December of 1891 under the orders of the mayor they had arrested 65 radical workers who were mostly known anarchists.

On the day of the 8th, for more than two hours people armed with pitchforks and torches paraded the streets shouting slogans. They attempted to win over the local garrison, but were unsuccessful in their efforts. Afterwords they attempted to liberate their colleagues from the local prison, failing to do so when the guard started firing upon them.

|

| TOMA DE JEREZ POR LOS CAMPESINOS 1892, THE SEIZURE OF SHERRY BY THE PEASANTS 1892, Museo Iconográfico de Jerez |

|

| Photo of the building at the top of Calle Larga, down which the rioters walked, Author's own work. |

The crowd was later dispersed when the army stepped in. The uprising resulted in mass arrests of 150 people and 4 executions via military tribunal, not a civil court, as it had been regarded as an insurrection.

|

| Execution by garrote of the 4 men, La Otra Andalucia |

The notion that the uprising was an anarchist plot to seize the city may be an overexaggeration. The vast majority of demonstrators were not workers they were bystanders that had joined the demonstration later. Anarchist organizations were usually used as a sort of scape goat or boogey man in order to make arbitrary arrests, as had happened in the infamous Mano Negra trials of 1883, where people were chosen at random, tortured until confession and subsequently tried. And many such elements can be found in this event.

For example, Félix Grávalo, an anarchist and bricklayer from Madrid, was subjected to torture and thus, agreed to testify against the men who would be later condemned to life sentences, his testimony being the only evidence of their implications in the violent riots. In one instance they marched him through the town and the fields at which points he pointed at those who had allegedly participated. Such was the case of José Romero Loma a schoolteacher and Antonio González Macías, who denied that they were anarchists, but got sentenced to life imprisonment. The police had used the testimony of Grávalo, that a barber Lamela was responsible for leading the uprising, his beliefs firstly being stated as unknown, however the Barbers Union at the time had been one of the most important local anarchist sections. In many cases apart from Grávalo’s testimony there was no evidence linking individuals to the uprising. Further proving that anarchism had been used as a scape goat in the events that occurred is the following correspondence between the mayors of Jerez and Cádiz as well as the mayor and rural police found in the local archives. The mayor stated two days after the events that the uprising was orchestrated by anarchists, despite not actually being informed by the police until a month later.

James Michael Yeaoman writes, that such rural uprisings in Andalusia were nothing new at that point in time. Similar incidents had taken place in previous decades, including attacks on Utrera and El Arahal in 1857 by local fieldworkers, and a revolt in Loja led by Rafael Pérez del Álamo. During the First Spanish Republic (FRE), uprisings took place in Sanclúcar de Barrameda and Alcoy, inspired by the FRE. He also mentions that the causal connection between the uprising and anarchist ideology is questionable, and has been a source of historiographical debate for over a century. Some local anarchists were definitely involved in the uprising, it was not a clear example of anarchist violence, nor was there a so called “Collective madness” or “Bestial urge” as stated by a contemporary Bernaldo de Quirós. The campesinos which marched down the streets of Jerez wanted to free the local prisoners and demonstrate their discontent with their current economic situation, not overthrow the old order.

Because there had been a media blackout preceded by mass arrests and repression beforehand, anarchist newspapers relied on reports from government and mainstream media as well as police reports. While La Tribunalia Libre said the uprising was anarchist in nature, most newspapers such as El Corsario and La Anarquia said it was not. Of the four men executed, two were not anarchist, but were blamed for the murder of Manuel Castro Palomino. After the executions there had been created a sort of martyrdom of the 4 killed, further fuelling the anarchist myth. About a year after the executions, an author Ricardo Mella published a detailed analysis of the uprising, where he found that the two men convicted of murder were not anarchists, a fact which had been overlooked by both the mainstream press and the military tribunals. While this didn’t change his view that the 4 had been “victims of bourgeois exploitation”, he did acknowledge it as evidence of a deliberate blurring of the facts by the government, which sought to link anarchism to all violent activity.

|

| The law legalising trade unions in 1887 |

The struggle for self-organization was also very prevalent during those times as labour unions were banned up until 1881, but even so after being legalized, organizations had to provide membership lists, which meant organized workers could be blacklisted, meaning that they were replaced by other forms of organizations such as consumer cooperatives but more on that later. Most manifestations at the time had the desire for association as their primary motive, a view shared by author Temma Kaplan, a prime example being the 1883/1884 Jerez Agricultural workers' strike and the 1883 and 1888 bakers strike in Puero de Santa María, which is also located in the Sherry triangle, where bakers demanded to be able to set their own rules, work environment, quality and wages, something reminiscent of medieval guilds, but more on that later.

Poverty and Insurrection

Finally, I would like to add that the same author states, the periodic upsurges of revolutionary activity in the south, so often attributed to poverty and millenarianism, actually seem to have occurred primarily in periods of relative prosperity or good harvests when organized workers flexed their muscles and the government counterattacked by suppressing the unions and the official anarchist organizations, not in periods of starvation a trend also apparent here as looking at the harvesting statistics, the harvests of 1891 and 1892 were exceptionally plentiful.

Earliest Mention of Regulations

From the Middle Ages to the time of the uprising there can be seen a steady continuum between the medieval guilds and the later workers organizations, for which the participants in the uprising struggled for. At first, I was, rather naively hoping to find a clear reference to the ancient forms of organization in the testimonies of the people involved, however that was not to be the case. However, what I did find was not only a material reference (structure and rules) to the old guild, but furthermore a formal reference (in the title).

At this point I should probably mention how guilds usually worked. Guilds were specialist organizations, allowing people of skilled professions to join together and better leverage their position on the market. Guilds usually standardized their production, meaning they determined the quality and quantity of production. For example, walking around a medieval town you could find several bakeries belonging to the same guild, that sold the exact same loafs of bread of the exact same quality and ingredients. Likewise, they determined work time rules, production quotas, insurance rules, hiring and firing rules. They also took care of the sick and elderly members of the guild as well as the families of deceased members. Most guilds were exclusionary organizations. One could only enter a guild after being recommended by an already senior member, meaning positions were usually inherited. The earliest form of regulation of wine production came when in 1483 the local city council promulgated The Ordinances of the Raisin and Grape Harvest Guild of Jerez, the first regulations governing the grape harvest, the characteristics of the casks, the ageing system and trade. It is also the first mention of a wine guild in the town of Jerez. The local city council published these Ordinances in order to standardize the production of wine as it had become a very lucrative business for the city, as its export to France, England and Flanders had already skyrocketed.

|

| The Ordinances of the Raisin and Grape Harvest Guild of Jerez (1483) |

|

| Thermes de Cluny, (1500), National Medieval Museum, Paris |

Winery Guild

The export of wine continued to increase and in 1733 a new organization called the Winery Guild was established. It functioned until 1834. Its dissolution did not come from poor trade or decline, rather the opposite. The organization was banned after a judicial proceeding called the “Pleito de los extractores" and stemming from later reports found in the archive it had become too powerful, some of its members having positions in the local government and subsequently harming the local treasury. Guilds were finally abolished in 1834 and definitively in 1836 by laissez-faire capitalist legislation. This in turn created a vacuum, which for most of the 19th century didn’t need to be filled.

|

| Founding document of the Winery Guild in 1733 |

Continuation, despite Restriction

However, this changed in 1863 when the small wine producers, who had faired pretty well up until now took a hard hit with the appearance of foreign, mostly British owned, monopolies as well as the Cobden treaty of 1860, which gave French wines a monopoly on the international wine market. While land dedicated to wine skyrocketed, the wine prices dropped, consequentially the once wealthy small wine proprietors became visibly indistinguishable from day labourers in all but title. Professions, such as coopers, blenders and pruners were facing an ever-larger stagnation in wages, some professions having to accept peace rates, rather than daily wages. Coopers especially had faced drastic change in demand and were being confronted with an ever-increasing proletarianization, as their work had been mechanized. With the absence of guilds as a traditional institution through which craftsmen defended their rights and set their own standards, labourers included in wine production were left defenceless. For its safety, the class of small proprietors turned to old forms of organizations and creating new ones, namely consumer cooperatives, protective associations, cultural organizations and credit unions, many even holding on to the guild organizations despite legal impediments. Thus, intentions to centralize work activities met resistance in Jerez, thanks to a powerful group of well-organized skilled vine-tenders, coopers, blenders and peasants. On the next slide we have two organizations which made agreements with the local government, the first regarding financing of drainage from 1840 and the second one from 1883 regarding the administration of a branch, both organizations bearing the name the Winery Guild.

A contemporary Fernando Garrido describes many such organizations in 1870, such as the La Fraternidad and La Igualdad consumer cooperatives with around 200.000 pesetas of capital each, the association of consumers and producers called La Abnegación founded in 1864 and based in Jerez de la Frontera, which focused on wine production as well as La Estrella serving the same purpose and La Primitiva construction society with 90 members and 30.000 pesetas capital and many more.

Furthermore, there were also many organizations, some within the anarchist federation, that had an organizational structure which strikingly resembles the guilds of old. For example, the cobblers who had an established hierarchy of apprentices and masters, as well as the aforementioned bakers, who struck for quality control, membership control, control over work and working hours. Anarchist federations were rather loose organizations, leaving a large autonomy to the individual organizations included within them, as they were organized bottom up, thus members of Anarchist federations didn’t necessarily follow anarchist ideology and most likely joined them for advanced protection through strikes.

At this point it should be mentioned, that there were two main branches of anarchism in Spain at the end of the 19th century. The first was anarcho-communism, which was generally associated with Peter Kropotkin’s doctrine. It envisioned a collective ownership of not only the means of production, but a common ownership of everything produced, meaning each person would get according to his or her needs, regardless of their contribution. Anarcho-collectivists on the other hand envisioned a society, where one would only be entitled to the fruits of labour only if he laboured himself, in other words, one must be productive, he must trade something in return, meaning that the elderly, children and others would be dependent on their families. Most of the skilled labourers were akin to anarcho-collectivist ideology, many joining the ambiguously named Union of Field Workers, which also included bakers, coopers and so on. The impoverished favoured anarcho-communism.

Finally, there were many organizations bearing the name “Gremio” or Guild. Even up until the 1920s, they held on to various elements of the guilds of old in their statutes and show a material continuation between the two. However, in some cases they also considerably diverge from the old rules which characterised the guilds, showing that this old fossil had to adapt to modern times, and more often than not carried the old name despite resembling contemporary forms of organization. Here are a few examples:

First off, we have the organization of Lithographic workers from 1919, which in art. 2 calls itself a guild. It also has the same restrictive entrance system, whereas one can only enter via recommendation and after the directory had accepted him. They also mention the incompatibility of having your own workshop and being a member of the guild as well as retaining the same hierarchy of masters and apprentices.

The second is the cooper’s guild, which mandates membership of the guild to anyone in that profession. It also retains the masters – journeyman - apprentice hierarchy as well as organizes its own Pension fund. They also create quantity restrictions, any overproduction being punished as well as cover the funeral costs of all former members, with mandatory attendance at the service, all of these elements being reminiscent of old guilds. In art. 28 they also forebay any member of working in a workshop, where the work is done by machinery, showing that they are trying to retain their skilled practice, which as mentioned before, faced ever-growing mechanization.

The third is the winery guild. Although this organization still has some elements of guild organizations, like defending the wine trade and issuing certificates it is mostly modernized so to speak, as it has an open membership and is focused on business.

And finally, we have the milk supplier’s guild. Here I found two main elements of guild organization, namely that the association itself provides the supplies and equipment as well as the fact that it exercises quality control and control over the sale of the milk produced.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the fact that there had been a long-lasting struggle for association, that anarchism was used multiple times as an excuse for preventing association and that hunger and desperation were not their main concern shows that the uprising of 1892 was not made up of anarchists trying to overthrow the old order, but rather by skilled workers and small proprietors desperately trying to self-organize, their organization bearing the name and a striking resemblance to the guilds of old, showing ironically their desire to retain old rights, and not to destroy the old order.

My further research will focus on the question: Did the people at that time make a direct reference to ancient rights / forms of organisation?

By Luka Držić

This contribution is part of the Ljubljana students' collective project The rights of association and assembly between assertion and resistance among Slovenes with an outlook to Spain in the long 19th century: villagers, workers, academics, lawyers, gymnasts, citizens at large (curated by Prof. dr. Katja Škrubej).

Archival Sources:

Archivo Municipal de Jerez de la Frontera

-1888-1893, M. 11, f. 271: Estadística de granos, vinos y olivares.

-1892, M. 11, f. 219: Boletín de Instrucción Pública, n. 136 y 139.

-1892, M. 11, f. 162: Sucesos de Enero, alocución de la Alcaldía.

-1892, M. 11, f. 163: Víctima de los sucesos de Enero de 1892, honras.

-1892, M. 11, f. 200: »El Alcalde«, periódico administrativo, n. 3.

-1892, M. 12 D, f. 1-8: Interrogatorios sobre asuntos de Jerez.

-1840, M. 4, f. 265: Gremio de Vinatería de Jerez.

-1834-1853, M. 2, f. 186-201: Gremio de vinateros. Documentos de la Junta Vinatera.

-1883, M. 9, f. 64: Acuerdo del Gremio de Vinateros sobre la Administración del ramo.

-AMJF Lº 300, Exp. 8942. Memoria referente a las principales causas que influyen en el malestar..., digitalizado en el siguiente enlace: http://www.jerez.es/fileadmin/Documentos/Archivo_Municipal/Folletos/151.pdf

-AMJF Lº 300, Exp. 8929

-AMJF Antecedentes de sociedades que se enviaron al gobernador civil: Lº604 Exp.13989

-AMJF Libros y Folletos, digitalizado en el siguiente enlace: https://www.jerez.es/webs-municipales/cultura-y-fiestas/servicios/archivo-municipal/libros-y-folletos-de-la-biblioteca-auxiliar

Archivo General Militar de Segovia

-Fondo 9.a (Justicia), legajos 2360-2365

Literary Sources:

-Kaplan Temma, ANARCHISTS OF ANDALUSIA, 1868-1903, (Princeton University Press, 1977)

-Garrido Fernando, HISTORIA DE LAS CLASES TRABAJADORAS. III. EL PROLETARIO, (Zero, 1970)

-Garrido Fernando, HISTORIA DE LAS CLASES TRABAJADORAS. IV. EL TRABAJADOR ASOCIADO, (Zero, 1971)

-Yeoman James Michael, PRINT CULTURE AND THE FORMATION OF THE ANARCHIST MOVEMENT IN SPAIN 1890-1915, (Department of History University of Sheffield, 2016)

-Kaplan Temma, THE SOCIAL BASE OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY ANDALUSIAN ANARCHISM IN JEREZ DE LA FRONTERA, (The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 1975)

-Naveiro León, EFECTOS DEL APOYO MUTUO EN LA ORGANIZACIÓN SOCIAL: GREMIOS, SINDICATOS Y ECONOMÍA SOCIAL Y SOLIDARIA, (Docta Complutense, 2023)

-Maestre Alfonso Juan, HECHOS Y DOCUMENTOS DEL ANARCHOSINDICALISMO ESPAÑOL, (Castellote, 1977)

-Carlos Seco Serrano, ACTAS DE LOS CONSEJOS Y COMISIÓN FEDERAL DE LA REGION ESPAÑOLA: (1870-1874), Volumes I and II, (Publicaciones de la Cátedra de historia general de España, Barcelona, 1969)

-Carlos Seco Serrano, CARTAS COMUNICACIONES Y CIRCULARES DEL III CONSEJO FEDERAL DE LA REGIÓN ESPAÑOLA, Volumes I, II and III, (Publicaciones de la Cátedra de historia general de España, Barcelona, 1972)

-Brey Gérard, LOS SUCESOS TRÁGICOS DE JEREZ DE LA FRONTERA DE 1892: UN BALANCE HISTORIOGRÁFICO, (Revista de Historia de Jerez, 1998)

-Avilés Juan, PROPAGANDA POR EL HECHO Y PROPAGANDA POR LA REPRESIÓN: ANARQUISMO Y VIOLENCIA EN ESPAÑA A FINES DEL SIGLO XIX, (Ayer, 2010)

Comments

Post a Comment