The European University EUTopia brings together

universities across the European continent, as well as partners from the whole

world. Students, academics and supporting staff live and work in a vibrant super-diverse

microcosm every day. Logically, norms and practices are influenced by

various layers of normativity. University research is increasingly targeted at

the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Funding is provided by the

European Union, national, regional and sometimes even local governmental

authorities, but also by multinational corporations. Universities have to abide

by laws, regulations, legal principles and judicial decisions emanating from multiple

jurisdictions, often not situated in the country wherein they are incorporated.

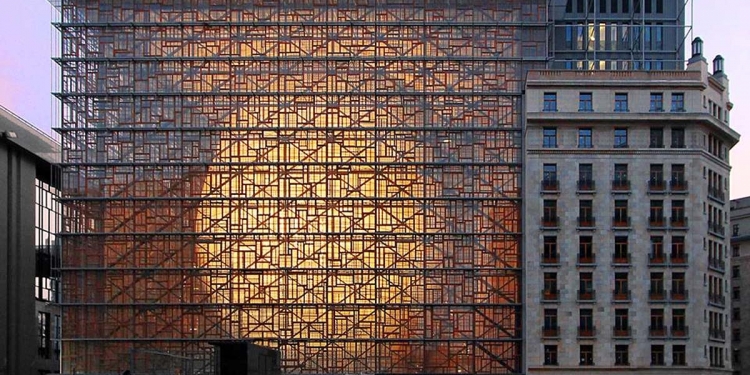

Nowhere is this ad hoc diversity so visible

as in Brussels, capital of the European Union, the federal state of Belgium, the

Brussels Region, the Flemish government (without actually being in the Flemish

region), and close to Atlantic Alliance NATO's headquarters. The presence of tens of thousands of diplomats,

European civil servants, researchers, businessmen and workers or citizens with

a non-European background is a contemporary form of international amalgamation. The

traditional opposition between Dutch and French (which characterizes modern and contemporary Belgian

history) is gradually being replaced by a multilingual reality, which

EUTopia as a truly diverse European university, also has at its heart.

The EUTopia Connected Learning Community Legal History assembles for the third consecutive year to exchange views on work-in-progress

in Brussels. On 14 March, the newspaper room of the Royal Library (KBR) will

host presentations and lectures for students from France (CY Paris, Prof.

Caroula Argyriadis-Kervégan), Slovenia (Ljubljana, Prof. Katja Škrubej), the UK

(Warwick, Dr. Rosie Doyle) and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Prof. Frederik Dhondt), with a keynote lecture from Prof. Cristina Nogueira da Silva (Nova

Lisboa). Our student’s presentations focus

on the use of sources of law, or legally relevant other sources, in order to

stir up comments and questions, and establish mutual links for the final online

exhibition.

(Al Rey Nuestro Señor: to the King our Lord, engraving of the Luyster van Brabant, a collection of local privileges alleged by the Brussels guilds against governor-general Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria, who administrated the Spanish Low Countries in the name of king Charles II of Spain (1661-1700); source: UGent/Google Books)

(Les Codes Belges, published by Servais and Mechelynck (1912)/Les codes en vigueur en Belgique (1842))

Before the advent of the nation-state and codification, Brussels was the administrative capital of the Southern Low Countries, a territorial ensemble that included the current Grand-Duchy of Luxemburg and parts of the present Kingdom of the Netherlands, but not the current belgian provinces of Limburg, Liège and other parts. This was not what we would call an independent state, but rather a personal union of polities with their own constitutional charters, case law, laws, and customary norms.

The statue of the Austrian governor-general Charles of Lorraine (1712-1780) and

his rococo palace (part of the Royal Library) are a reminder of this past. The

monarch’s counsellors and lawyers, but also foreign envoys and bankers, coexisted

and mingled with local elites. The heyday of Antwerp’s port (succeeding

Bruges’ and earlier Ghent’s) attracted trading nations. Their relationships were governed by a variety of legal sources. Conversely, ‘Flemish’

merchants and artists benefited from mobility within the Habsburg world.

From 1531 on, a governor-general represented the sovereign, who either itinerated across Europe (Charles V, who was also Duke of Krain or Carniola [the major part of present-day Slovenia]) or reigned from the Escorial in Spain (Philip II) or -after 1715- Laxenburg and Schönbrunn in Austria (Charles VI, Maria Theresia, Joseph II). Although the sovereign was not physically present, he remained restricted by the equivalent of German territorial Landesverfassungen, typically entailing the Estates' mandatory consent to taxation.

Legislative acts legally emanated solely from the sovereign, as Duke

(or Duchess) of Brabant, Count (or Countess) of Flanders, Lord (or Lady) of

Mechelen, Count (or Count) of Namur… Debates on legislation could be initiated ("bottom-up") by local elites, included advice by local lawyers, but were decided at

a distance. However, the sovereign’s personal priorities and ideological inspiration,

but also examples from other territories under his or her domination, could influence

the legislative program for the Low Countries, as the case of the Enlightened

Emperor Joseph II

illustrates: if the judiciary and procedure could be reformed in Milan, why then not in Brabant or Luxemburg ?

The position of the current Belgian territory at

the crossroads of continental and maritime trade sketches other gateways

for the circulation of persons, goods and ideas. This fruitful and unique locus

as hub of European and world trade also entails geopolitical risks, as the

story of the General

Imperial Company in Ostend (1722-1731) illustrates. This chartered company

was entrusted with an exclusive right by Emperor Charles VI to sail to India

and China, and engage in trade. The Emperor could ground this decision in the law of nature, appealing to freedom of navigation on the high seas. The Ostend Company’s investors in Antwerp (whose

trade suffered from the separation of the Low Countries), Ghent and Brussels

expected to reap the benefits of a balancing exercise between offer and demand

on markets separated by thousands of kilometres: it upset the European tea

market, causing jealousy and anger in Amsterdam and London.

International pressure caused the suspension

and retraction of the Ostend Company’s privilege, illustrating that territories

on the periphery of a composite monarchy could be sacrificed to the

monarch’s higher interests. Proposals to move the company to Triest (the

nearest harbour to Krain/Carniola) were seen as impracticable by the Ostend Company’s

directors. Charles VI (another monarch shared by Brussels and Ljubljana/Laibach)

preferred the recognition of his order of succession (prioritising his daughter Maria Theresia) across the Habsburg lands

to the protection of his ‘Belgian’ citizens. Conversely, Joseph II’s choice to remain

neutral in the American War of Independence (1776-1784) and the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784) attracted ships to Ostend,

drawing mercurial benefits from the war between Britain, France, the Dutch Republic and

Spain. This, in turn, linked the ‘Belgian’ territories to the transnational

phenomenon of the slave trade and the sale of arms.

Belgian history provides further fascinating examples whereby power relationships are expressed in the actors’ legal imagination, such as Belgian feminist activists’ criticism of the paternalistic Civil Code and their political marginalisation, or the legal category of ‘indigène’ in colonial Congo, a space governed by rules and institutions conceived by lawyers trained and socialized in Belgian legal culture.

.JPEG)

.JPEG)

Comments

Post a Comment