LJUBLJANA CASE: The diversity of the tabori rallies movement in Slovene lands: Reactions to the (non)radicality of collective rights at massive assemblies

Introduction

The aim of my research is to illustrate the diversity of the tabori movement in the Slovene lands through the lens of its various demands and the resolutions adopted at mass gatherings.

Although the title references reactions to demands concerning collective rights, my analysis will focus exclusively on comparing the specific demands at different tabori. The tabori movement sparked intense debates and frequently led to tensions between Slovene and German-language newspapers. However, an independent research project would be needed for such comprehensive study.

Between 1868 and 1871 a total of 18 tabori took place within Slovene territory. The term tabor (plural: tabori) could be roughly translated as "rally"; however, to preserve its historical context I will be strict with using the Slovenian term.

What were tabori?

Tabori were mass political gatherings held in open spaces, significantly contributing to the development of a culture of public assembly. These gatherings provided a forum where large segments of the population could exercise a form of plebiscitary expression of opinion. As such, the tabori movement marked a crucial turning point in contemporary perceptions of democratic processes within bourgeois monarchies of the long 19th century. Notably, they extended participation to individuals without voting rights, predominantly rural inhabitants, who, importantly, constituted the majority of the Slovene-speaking population. Tabori also bridged the social and class divide between the bourgeoisie and the peasantry—an obstacle that had previously hindered efforts to unify the Slovenes.

|

| Figure 2: A simplified timeline showcasing important events during the 1868-1871 tabori movement |

Historical context

During the period following the end of Napoleonic Wars, Slovenes resided within the Austrian Empire – yet were administratively and politically fragmented across multiple historical provinces (Länder, terrae, dežele). Among these only Carniola (Kranjska) was predominantly Slovene. A significant proportion of the population within Slovene ethnic territory was monolingual in Slovene, whereas German predominated as the language of communication and correspondence among the bourgeois and aristocratic intelligentsia.

In 1848, a revolutionary wave, known as the "Spring of Nations" swept across Europe. It was in this context that Slovenes formulated their first political program, advocating for a unified Slovene territory (Zedinjena Slovenija), a demand promoted through a petition movement of 1848. This political initiative sought the unification of all Slovenes into a single administrative-political entity with its own representative body within the Austrian Empire. Such a restructuring would result in the dissolution of the historical lands. Additionally, the movement called for an enhanced role of the Slovene language in education and public administration. The March Revolution of 1848 was ultimately suppressed the following year.

|

| Figure 3: Peter Kozler's Map of the Slovene Land and Provinces, drawn during the Spring of Nations in 1848. |

In 1867, the introduction of the Dual Monarchy transformed the homeland of the majority of Slovenes. In the year of 1871 Europe witnessed the unification of Germany and Italy. The tabori movement has been characterized as one of the most significant political expressions of Slovene national consciousness in the 19th century. Its emergence was facilitated by the Statute of the Association for defending national rights in Ljubljana (1867) and by the Statute on the Freedom of Assembly (November 15th, 1867), which legalized political gatherings.

The organizers and speakers at tabori were important individuals. This group included clergy, legal professionals, physicians and members of the Slovene intelligentsia. Among the most prominent figures were the Ljubljana-based lawyer Dr. Valentin Zarnik, the physician Dr. Josip Vošnjak, the Brežice-based lawyer Radoslav Razlag, and Dr. Janez Bleiweis, a veterinarian and editor of the influential journal Novice. Devoted tabori participants were also members of the Sokol Association (for more information on the Sokol Association see Bogdan, Domen: Defying Organizational Challenges and Collective Resilience at the Turn of the 20th Century: The Case of the Sokol Association in Styrian Ljutomer and Benčič, Teja: The Sokol Association in Ljubljana, the capital of Carniola: Physical Education as a Means of Political Engagement in the 19th and 20th Centuries?).

|

| Figure 4: Some of the most prominent members of the Slovene intelligentsia on the postcard for Vižmarje tabor (1869). |

Tabori program demands

At the core of all tabori programs was the demand for the actual implementation of §19 of the Imperial Basic Statute on the General Rights of Citizens, which stipulated that all national groups within the empire were equal and that each had an inalienable right to preserve and cultivate its national identity and language. The unifying theme across all tabori demands was the realization of the program goals first articulated in 1848 with the call for Zedinjena Slovenija. Tabori also put forward both nationwide and localized proposals.

The (non) radical nature of tabori demands: A case study of three tabori

My research focuses on three specific tabori gatherings, which I consider particularly significant. I compare the demands put forth at the first tabor in Ljutomer, the second and most radical tabor in Žalec, and, finally, the best-known and most widely attended tabor in Vižmarje. While the demand for Zedinjena Slovenija was the core of the tabori movement, it is noteworthy that at the first two gatherings—Ljutomer and Žalec—it was listed only as the fifth point in their programs.

The Ljutomer tabor program devoted its first three points to the issue of linguistic rights, with the call for Slovenian unification serving as the program’s concluding and climactic demand. The Žalec tabor, held just over a month later, followed a similar structure but displayed a greater assertiveness in its demand for Slovene to become the exclusive official language in public administration and education. Furthermore, the Žalec resolution called for the establishment of a special commission to oversee the implementation of linguistic policies. Specifically, it stipulated that civil servants must acquire proficiency in both written and spoken Slovene within six months and that the commission would provide guidance and expertise in the use of the language.

|

| Figure 5: A 20th century postcard from Žalec, where the second tabor was located. |

The demand for Slovene-language education was nearly identical at the first two tabori. The calls for the use of Slovene in schools and public administration at the Vižmarje tabor were presented in a more straightforward manner, raising the question of whether certain advances had already been achieved in these areas or whether some demands had been abandoned in the meantime. Additionally, Žalec tabor introduced demands for agricultural and economic schools as well as the establishment of a Slovene economic society. The final demand at the Vižmarje tabor echoed the Žalec resolution’s focus on improving agriculture and the economy but introduced a new proposal: the establishment of a Slovene insurance society. The wording of the demand for Zedinjena Slovenija also differed between the first two gatherings. The Ljutomer tabor simply called for the legal unification of Slovenes under a national administration, whereas the Žalec tabor framed this demand in stronger nationalistic terms. At the Vižmarje tabor, the demand for Slovene unification occupied the first position in the program.

|

| Figure 6: Printed invitation for Vižmarje tabor (1869). |

The Right to Assembly: Statute on the Freedom of Assembly (November 15th, 1867)

Of particular interest to my research is the right to assembly, which was codified in the Statute on the Freedom of Assembly (Gezetz über die freie Ferzammlung). This statute legalized political gatherings and provided the legal foundation for the tabori movement. By June 1868, Slovene journals were already reporting on discussions about organizing tabori, likely inspired by similar gatherings in the Czech lands. The term tabor itself was used for such Czech assemblies, but it was already familiar to Slovenes, as it had historically referred to anti-Ottoman fortifications. Organizers drew parallels between this historical use and the contemporary struggle to defend Slovene identity against Germanization and Italianization.

| |||

| Figure 7: Gesetz über die freie Versammlung (Statute on the Freedom of Assembly (November 15th,1867). | For design purposes only, I have included a painting of cca. 1840s K.K. Gendarmerie. |

The 1860s were often perceived as a period of complete political liberalization. However, despite extensive new legislation permitting the establishment of political associations, freedom of assembly, and an expansion of Slovene journalism, the practical application of these rights was frequently obstructed. For example the journal Slovenski narod reported on May 15, 1869, that the imperial-royal land administration in Ljubljana had objected to the announcement of the Vižmarje tabor, published in the journal Novice. Authorities decreed that invitations could be made public only after the official permission had been granted. In response, Slovenski narod mentioned Articles 2 and 3 of the assembly statute, which required that gatherings be announced in writing at least three days in advance, with authorities required to immediately confirm receipt. Should permission be denied, authorities were obligated to provide written justification.

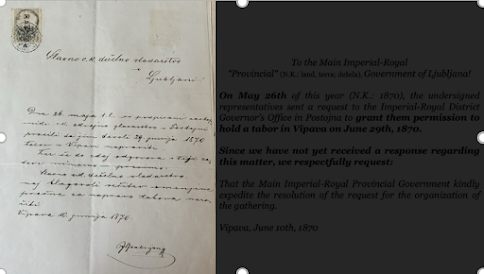

However, in practice tabori organizers were often left without official responses for extended periods, forcing them to publish invitations in advance, lest they risk a low turnout on the day of the event. My own archival research at the Archive of the Republic of Slovenia revealed similar administrative obstacles in organizing the tabor in Vipava.

|

| Figure 8: Letter to the Main Imperial-Royal Provincial Government of Ljubljana from Vipava, dated June 10th, 1870 |

One notable case, reported in the press involved a letter from a patriot in Metlika (Carniola), describing the unacceptable actions of a political commissioner, who allegedly tore down posters announcing tabori at Kalec and Vižmarje. According to the report, the two officials even entered čitalnica (“reading club“)’s reading rooms to remove indoor posters. This raises the question of whether such incidents, as widely reported in Slovene newspapers, might have contributed to the massive attendance at the Vižmarje tabor. For more information on čitalnice see Benčič Teja: From reading club to political association after 1848/1867 in Ljubljana, the capital of Carniola: local initiative in a multi-level governmental space?

Further research questions

During my research I have come across severeal potential research questions, such as:

- Reasons behind the massive attendance at 1869 Vižmarje tabor

- Reactions to the (non)radicality of collective rights at tabori: a closer study on journal reports in Laibacher Tagblatt and Bleiweis’ Kmetijske in rokodelske novice

- What caused the downfall of tabori after 1871?

Conclusion

The tabori movement in the Slovene lands was an important moment in the political and national awakening of Slovenes in the 19th century. By analyzing the demands at different tabori, my research has illustrated the movement’s internal diversity, demonstrating that its objectives ranged from broad national aspirations—such as the unification of Slovenes to localized socio-economic concerns. The comparative study of the tabori at Ljutomer, Žalec, and Vižmarje underscores the evolving nature of these demands. While the goal of Zedinjena Slovenija remained constant, variations in emphasis and tone highlight the complex interplay between national identity, political pragmatism, and regional particularities. Žalec tabor, for instance, emerged as the most radical in its linguistic and administrative demands, whereas Vižmarje tabor prioritized national unity more explicitly, reflecting both a maturation of the movement and a reaction to political pressures. In conclusion, the tabori movement was instrumental in shaping Slovene political culture by bridging the social divide, fostering democratic engagement beyond the electorate, and reinforcing the legitimacy of Slovene national demands.

By Nives Košnjek

This contribution is part of the Ljubljana students' collective project The rights of association and assembly between assertion and resistance among Slovenes with an outlook to Spain in the long 19th century: villagers, workers, academics, lawyers, gymnasts, citizens at large (curated by Prof. dr. Katja Škrubej).

Sources

Secondary sources

Čeč, Dragica (2018). Tabori na Slovenskem in družbene razmere v šestdesetih letih 19. stoletja. Zgodovina v šoli, volume 26, issue 2, str. 3-22. URN:NBN:SI:DOC-C7SOL5N4 from http://www.dlib.si

Granda, S. (2019). Vižmarski tabor: tabor vseh taborov (1. izd., str. 64). Etnološko društvo Vižmarje.

Rajšp, Vincenc (2020). Taborsko gibanje na Slovenskem 1868-1871. Časopis za zgodovino in narodopisje, letnik 91 = n. v. 56, številka 2/3, str. 12-39. URN:NBN:SI:DOC-62PM5AN3 from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenska kronika XIX. stoletja. 1861-1883. Ur. Janez Cvirn. Ljubljana: Nova revija 2003. 412 str

Taborsko gibanje na Slovenskem: [ob 150. obletnici 1. slovenskega tabora v Ljutomeru] (Ponatis publikacije z izbranimi vsebinami po izdaji leta 1981, str. 58). (2018). Splošna knjižnica.

Primary sources

Journals

Slovenski narod (27.05.1869), letnik 2, številka 61. URN:NBN:SI:doc-CII05S1C from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski narod (25.05.1869), letnik 2, številka 60. URN:NBN:SI:doc-X8P0ZF1D from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski narod (20.05.1869), letnik 2, številka 58. URN:NBN:SI:doc-U02LRDDF from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski narod (22.05.1869), letnik 2, številka 59. URN:NBN:SI:doc-6994C82R from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski narod (15.05.1869), letnik 2, številka 57. URN:NBN:SI:doc-TD0BZWA7 from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski narod (13.05.1869), letnik 2, številka 56. URN:NBN:SI:doc-JLJWB5YN from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski narod (14.08.1868), letnik 1, številka 57. URN:NBN:SI:doc-Y4M5W3E6 from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski narod (23.06.1868), letnik 1, številka 35. URN:NBN:SI:doc-7CPH14DV from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski narod (13.08.1868), letnik 1, številka 56. URN:NBN:SI:doc-NZLS1JAW from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski narod (11.08.1868), letnik 1, številka 55. URN:NBN:SI:doc-UDUOBLOH from http://www.dlib.si

Kmetijske in rokodelske novice (16.09.1868), letnik 26, številka 38. URN:NBN:SI:doc-9VF01OVH from http://www.dlib.si

Kmetijske in rokodelske novice (19.05.1869), letnik 27, številka 20. URN:NBN:SI:doc-GX52T51P from http://www.dlib.si

Kmetijske in rokodelske novice (26.05.1869), letnik 27, številka 21. URN:NBN:SI:doc-X6SK60SB from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski gospodar: podučiven list za slovensko ljudstvo (13.08.1868), letnik 2, številka 33. URN:NBN:SI:doc-77P5ORDX from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski gospodar: podučiven list za slovensko ljudstvo (20.08.1868), letnik 2, številka 34. URN:NBN:SI:doc-8KUJ81IK from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski gospodar: podučiven list za slovensko ljudstvo (03.09.1868), letnik 2, številka 36. URN:NBN:SI:doc-5IUSH73L from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski gospodar: podučiven list za slovensko ljudstvo (10.09.1868), letnik 2, številka 37. URN:NBN:SI:doc-PUFNNBEJ from http://www.dlib.si

Slovenski gospodar: podučiven list za slovensko ljudstvo (17.09.1868), letnik 2, številka 38. URN:NBN:SI:doc-HKEOKYR7 from http://www.dlib.si

National Archives of the Republic of Slovenia: Archive of the district administration of Postojna. AS 136. P/14 – P/28

Comments

Post a Comment