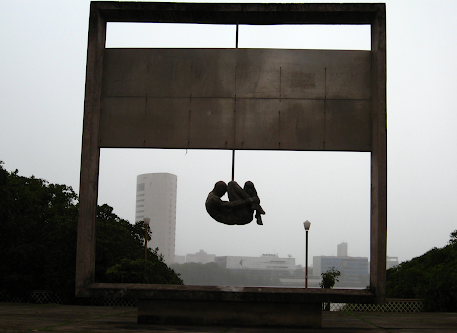

photo by @Marcusr

The "Monument Tortura Nunca Mais” stands in the centre city of Recife, the capital of Brazil’s north-eastern state of Pernambuco, as a memorial to the torture victims of the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964-1985). In 1964, Brazil came under a military dictatorship when José de Magalhães Pinto, Adhemar de Barros and Carlos Lacerda, deposed President João Goulart. Its purpose was to suppress left-wing political sentiments supposedly encouraged by Goulart and set up a regime that targeted social movements, political organisations and individuals that preached communist ideals.

The sculpture was created by the artist and architect Demetrio Albuquerque and completed in 1993. It is estimated that over 20,000 people were tortured by the military and secret police agencies, the Agência Brasileira de Inteligência (ABIN) and the Serviço Nacional de Informações (SNI). Activists fighting the dictatorship through armed and non-violent resistance were among those tortured. Testimonies collected in the Amnesty International archives reveal how people captured were subjected to hours, days, weeks, or months of torture for as little as having been heard criticising the regime. The terrifying torture methods that were used on prisoners included but were not limited to sleep and sensory deprivation, starvation, rape and sexual abuse, electrocution, beatings, the burning of cigarettes on the skin and even the insertion of starved rats into orifices. The most common method of torture was the pau-de-arara (“the wood of the macaw”), which involved suspending someone tied by their wrists and the back of their knees from a horizontal metal pole for days while they were physically beaten.

The Brazilian military and secret police were trained extensively in methods of interrogation and torture by the CIA, and abroad in the notorious “School of the Americas” in Panama. My research using material recently made available in the National Archives in London from the Information Research Department (IRD), a covert, Cold War propaganda department of the British foreign office, revealed the British involvement in teaching torture. It demonstrated that advisors from the U.K. military also travelled to Brazil and trained Brazilian military officials on methods of torture. The IRD was also involved in providing materials to Brazil to rouse the fear of communism. This culture of fear made distinct divisions between 'good' capitalism and 'bad' communism, further heightening the tensions among the public to be wary of any communist expression. The regime of fear was created both by the British and Brazilians and the testimonies of several individuals show that they were ‘ordinary’ people who were kidnapped as they went to grocery stores, police or military invasions of homes belonging to people who just knew of ‘communists’, or simply teaching a curriculum based on other countries besides Brazil. One man was walking home with a magazine in his hand about how “students shouldn’t accept the re-introduction of school fees” because it restricted education to the elite class. Once arrested, he was “submitted to the parrot’s perch” and exposed to “ferrule blows to all body parts”.

The issue of memory and accounting for past human rights violations continues to be of paramount concern in Brazil. Due to the Amnesty laws, which were passed by the military regime in 1979 and upheld by Brazil's Supreme Court, it has shielded those who committed "political crimes" between September 1961 and August 1979 from prosecution, making it increasingly difficult for victims of torture to seek justice. It was not until 2021, that a Brazilian court issued the first conviction of a state agent for human rights abuses committed during the dictatorship of 1964 to 1985. A judge in São Paulo sentenced retired police officer Carlos Alberto Augusto to 2 years and 11 months in prison for the kidnapping of Edgar de Aquino Duarte.

The conditions surrounding Amnesty Laws are intriguing. On one hand, it excuses those who were simply brainwashed into believing the extremities of communist danger in Brazil - though not excusing their behaviour and violent crimes, it allows space to consider the dictatorship’s violent effects on those who believed in it. But on the other hand, it protects those who committed these heinous acts of torture.

What does the statue do? It manifests a metaphor of justice still awaiting, in the balance of being delivered slowly. A significant part of this truth process is revealing the truth about British collusion with the regime. Recently, UK, Deputy Prime Minister Dominic Raab stated: “ I squarely believe that we ought to be trading liberally around the world. If we restrict it to countries with FCHR- level standards of human rights, we’re not going to do many trade deals with the growth markets of the future”.This comment highlights not only the avoidance of addressing human rights abuses but it further silences the history of Britain's role in directing some of the horrific violence in Brazil. Britain has never been held accountable for its direct interference but there is a growing literature about the IRD and the procurement of torture methods in Brazil, exemplified by the works of, Geraldo Cantarino’s Segredos da propaganda anticomunista and A ditadura que o inglês viu, and João Roberto Martins Filho’s Segredos de Estado. O Governo Britânico e a Tortura no Brasil. 1969-1976 . These works are not translated or well known in the UK, even though they provide valuable insight into the collaboration between Brazil and Britain. Britain continues to trade with Brazil, even under the current President Jair Bolsonaro. His speech on 17 of April 2016 when Dilma Rousseff, the President at the time and a victim of the torture during the dictatorship, was facing impeachment, came out in favour of impeachment with the following words, “For the memory of Colonel Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra, the terror of Dilma Rousseff, for the Caxias’ Army, for the armed forces, for Brazil, and for God above all, my vote is ‘yes.’”.The culture of fear still continues on both sides; torture in prisons continues, and Colonel Paulo Malhaes, a torturer who spoke about his involvement in the regime, was murdered during a burglary at his home soon after giving evidence, showing there are efforts to silence those who reveal the truth.

Whilst the dictatorship ended in 1985, the search for the truth is incomplete left.

Written by Mehr Ahamad

Archdiocese of Sao Paulo, ‘A Shocking Report on the Pervasive Use of Torture by Brazilian Military Governments, 1964-1979, Secretly Prepared by the Archiodese of São Paulo’, (1998)

Blakeley, Ruth, “Why Torture?” Review of International Studies, 33.3, (2007), 373–94, <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40072183> [Accessed 3 May 2022]

Buchanan, Emily, ‘How the UK taught Brazil's dictators interrogation techniques, BBC, 30 May 2014 < https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-27625540> [3 February 2022]

Canofre, Fernanda, "“We have to Talk about it”: Why Brazil must Confront the Crimes of its Military Period." World Policy Journal, 33. 4, (2016), 96-100. < muse.jhu.edu/article/645266.> [13 April 2022]

Cormac, Rory, ‘The currency of covert action: British special political action in Latin America, 1961-64’, Journal of Strategic Studies,

<10.1080/01402390.2020.1852937>

Darius, Rejali, ‘Supply and Demand for Clean Torture’ in Torture and Democracy. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), pp. 405-446. De Gruyter EBOOK

Endo, Paulo, ‘Torture: Notes and Perspectives in a Context of Governmental Support for Gross Violations of Human Rights in Brazil.’ Portuguese Studies, 37.1, (2021), p. 47-57,

< doi:10.1353/port.2021.0004.>

Huggins, Martha K., ‘Legacies of Authoritarianism: Brazilian Torturers’ and Murderers’ Reformulation of Memory.’ Latin American Perspectives, 27. 2, (2000), 57–78, <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2634191> {Accessed 3 May 2022]

Kelly, Patrick William., ‘Torture in Brazil. Sovereign Emergencies: Latin America and the Making of Global Human Rights Politics’, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2018), pp. 21–60, Cambridge Core Books

McEvoy, John, ‘Britain and Brazil’s Dictatorship’, Brasil Wire, 9 July 2020 <https://www.brasilwire.com/britain-brazil-dictatorship/> [2 February 2022].

McEvoy, Kevin J., Before the rubble: Britain’s secret propaganda offensive in Chile (1960-1973), Contemporary British History, 35:4 (2021), 597-619, < 10.1080/13619462.2021.1971080>

Richards, Lee, ‘The rainbow in the dark: assessing a century of british military information operations’, 41-66, < https://stratcomcoe.org/cuploads/pfiles/lee_richards.pdf>

Wilford, Hugh, ‘The Information Research Department: Britain’s Secret Cold War Weapon Revealed.’ Review of International Studies, 24.3, (1998), 353–69, <http://www.jstor.org/stable/20097531>

Woodcock, Andrew,‘Dominic Raab tells UK officials to trade with countries which fail to meet human rights standards in leaked video’, online video recording, Independent, 17 March 2021,<https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/dominic-raab-trade-human-rights-b1818126.html >[23 April 2022]

Comments

Post a Comment